ORIENTING

The theory of developmental evaluation that undergirds CAM outlines orienting and guiding principle development as the first two steps in the process of evaluation. Both of these are necessary because of the dynamic and adaptive nature of the process. The process of orienting and creating guiding principles allows the evaluative team to have elements that center the process when things get complex, off-track, or divisive.

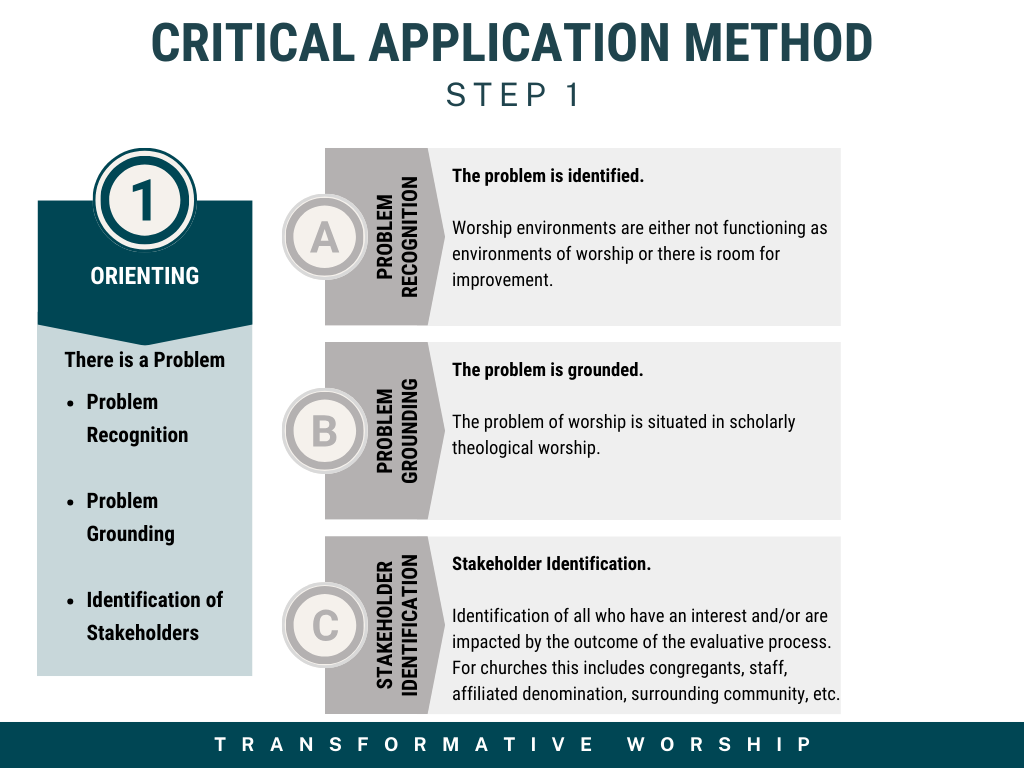

Step 1, Orienting, has three components – Problem Recognition, Problem Grounding, and Stakeholder identification.

Problem Recognition: There is a problem with worship as it is – either worship is not leading to transformation or there is room for improvement.

Problem Grounded: The problem is grounded in theological scholarship. Interventions that aim to improve worship occur regularly. What is not happening is the regular practice of rooting interventions in both experience and theological scholarship.

The theological framework that orients and grounds this problem of worship for CAM is:

- Theology of the Church

- The church is not the meeting itself or the meeting place, but rather, the community of individuals. Because the church is a community of individuals, it is important to understand that the relationship between God and the community and God and each individual is a key aspect in the right formation and function of the church.[1]

- Theology of Worship

- The work of the church involves the active participation of its members; but, the work should always be in response to God’s leading and a recognition that it is through God’s power that the work is ultimately accomplished.[2]

- As a response to the initiative and power of God, the work of the church is meaningful, as not because of what they were doing, but “because of what God is doing in and through His Spirit.”[3]

- Worship is, first and foremost, a response to God “because it is God who always take the initiative.”[4]

- Worldview

- A worldview is “like a mental map that tells us how to navigate the world effectively.”[5]

- Worldview functions as a lens for interpreting the world, rather than a philosophy. It influences how individuals, organizations, and communities perceive and assess things, and ultimately guides their decision-making.

- Culture is central in the formation of an individual’s worldview.[6]

- “There is not now, nor ever has been, a human being who is not totally immersed in and pervasively affected by some culture.”[7]

- The significance of this fact lies in the impact of one’s worldview on both their perception of reality and their responses to life’s events. Simultaneously, individuals are frequently unaware of the role culture plays in shaping their beliefs.

- A worldview provides answers to three fundamental questions:

- Creation – How did it all begin? Where did we come from?

- Fall – What went wrong? What is the source of evil and suffering in the world?

- Redemption – What can we do about what went wrong? How can the world be set right again?[8]

- The way in which these questions are answered directs how others and the world is interpreted and understood. Therefore, worldview influences our morals, ethics, and values – impacting how individuals make decisions, interact with others, search for purpose, and find meaning in life.

- Geoffrey Wainwright argues that the Christian church has both the power and responsibility to “transmit a vision of reality which helps decisively in the interpretation of life and the world.”[9]

- Secular Culture

- Taylor’s influential 2007 book, A Secular Age, has become a foundational text utilized by scholars from various academic domains, serving as a fundamental guide for comprehending the development of modern culture and its historic evolution.

- Central to Taylor’s work is the idea that our current era is secular in character, and as such, he designates the era in which we live today as a “Secular Age.”[10]

- As outlined by Taylor, secularity can be categorized into three distinct modes: Secular 1, Secular 2, and Secular 3.

- Secular 1: Public spaces “have been allegedly emptied of God, or of any reference to ultimate reality.”[11]

- Secular 2: In secular culture, there is a noticeable decline in religious belief and practice, with individuals turning away from God and disengaging from church participation.[12]

- Secular 3: Secularity does not signify the absence of God and religion in the modern era; rather, it signifies a transition from a society wherein “belief in God is unchallenged and, indeed unproblematic, to one in which it is understood to be one option among others.” And meaning making finds its ultimate authority in the individual.[13]

- Disenchantment

- Before our modern age, it was taken as a given that God and spirituality impacted all aspects of life – science, politics, economics, faith, etc. In an enchanted world, “the world of spirits, demons, and moral forces”[14] was inherently apart of all aspects of life. But, in a disenchanted world, there is not a reality that transcends what can be seen, experienced, or tested by man.

- “Personal control over then environment” has become the top value that American’s live by. As such, Americans believe that humanity has complete control over their own fate stating that any other type of thinking is “backward, primitive, or hopelessly naïve.”[15]

- Individualism

- In a secular world, there are no final goals beyond human flourishing nor any allegiance to anything else beyond this flourishing.”[16]

- individualism is marked by a search for authenticity in which “the world assumes each person has his or her own right to define for himself or herself what it means to be human.”[17]

- Authenticity is “to see ourselves on a journey to make meaning, seeking to be loyal (often only) to what speaks to us, to what engages us, to what moves us.”[18]

- A disenchanted world not only permits individualism and the pursuit of individual authenticity, it actively promotes this way of existence by eliminating a single overarching ideal. It becomes the individual’s responsibility to navigate their unique path towards wholeness and spiritual depth, with a primary focus on personal experience.[19]

- Theology of Creation

- How we are created matters.

- Embodied

- “Most of us, especially Westerners, think of ourselves as minds with a body attached” which is dangerous because “human beings are physical bodies; that’s how God created us.”[20]

- When the body is not valued as an important and meaningful part of God’s creation, the body becomes nothing more than a burden for the spirit. The spirit of a person, in turn, comes to be seen as a transcendent ego separated from the phenomena that it studies.”[21]

- Communal

- Because the very nature of God is triune and exists in eternal communion as God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, humans, too, are created to live and flourish in community.[22]

- God does not exist outside of community and, thus, neither can humans. In fact, Zizioulas goes so far to contend that the communal nature of God is so vital to the nature of God that “there is no true being without communion.”[23]

- For humans, the ability to live into their inherent communal nature requires relationship with both God and others.

- Driven by Love

- The Cartesian theory of “I think, therefore I am” is founded on the idea that humans are first and foremost thinking beings and therefore what is most important is facilitating the acquisition of knowledge.

- Thinking is, indeed, an important part of what drives human behavior. However, “thinking” is not the crux of what drives human behavior; neither is the idea of human as “believer” wherein our worldview or beliefs “govern and condition our perception of the world.”[24]

- The “thinker” and “believer” models are only part of what drives the human, not the whole; and that the whole of what drives human behavior is, instead, love.

- It is what we love, what we desire, that “governs our vision of the good life, what shapes and molds our being-in-the world” and our “ultimate love is what we worship.”[25]

- Habituated

- Habituation – the process of becoming accustomed to something – is the primary process by which our worldview/view of the good life is developed.[26]

- “Research has found that habits “emerge because the brain is constantly looking for ways to save effort,” and, in fact, “the brain will try to make almost any routine into habit, because habits allow our minds to ramp down more often.”[27]

- Habits are formed, literally wired in the neurons of the human brain, from the daily experiences of the human through a “self-organizing process based on continual feedback from action in the world.”[28] It is as humans engage in the rhythms, values, and actions of individuals and communities – what Smith would call liturgies of the world – that the open neural networks of the human brain become coded.[29]

- The liturgies of the world “are what shape humans in unconscious ways and orient them toward a particular telos.”[30] Liturgies of the world teach us what the “vision of the good life” is and program our brain to love and desire the things that would bring that vision to life.

Stakeholder Identification

Stakeholders are all of the people and organizations who have an interest in and/or are impacted by the outcome of the process.[31] In the church, typical stakeholders are the congregants, the staff, any affiliated denomination, the faith community at large, and the surrounding community (as transformed congregants are able to benefit the community and non-transformed congregants can have a negative impact on the community). Each stakeholder analysis needs to be contextually based and stakeholders need to be held at the forefront of the process. For CAM is not an abstract process; rather, it is work that should have a very real impact on the lives of others.

References:

[1] Justo L. González and Zaida Maldonado Pérez, An Introduction to Christian Theology (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2002), 102.

[2] Williams et al., Theological Foundations of Worship, 174.

[3] Jonathan Landry Cruse, What Happens When We Worship (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Reformation Heritage Books, 2020), 18

[4] Cheslyn Jones, ed., The Study of Liturgy, Rev. ed (London: New York: SPCK ; Oxford University Press, 1992), 9.

[5] Nancy Pearcey and Phillip E. Johnson, Total Truth: Liberating Christianity from Its Cultural Captivity, Study guide edition (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 2009), 23.

[6] Pearcey and Johnson, 25.

[7] Kraft, 81.

[8] Kraft, 53.

[9] Wainwright, Doxology, 2.

[10] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, First Harvard University Press paperback edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2018), 3.

[11] Taylor, 2

[12] Taylor, 2.

[13] Taylor, 3.

[14] Taylor, 26.

[15] Kohls, L. Robert, “The Values Americans Live By,” 2.

[16] Taylor, 18.

[17] Root, “Faith Formation in a Secular Age.”

[18] Root, Location 275.

[19] Taylor, 507.

[20] Frank C. Senn, Embodied Liturgy: Lessons in Christian Ritual, 2016, 3.

[21] Senn, 5.

[22] Jean Zizioulas, Being as Communion: Studies in Personhood and the Church, Contemporary Greek Theologians, no. 4 (Crestwood, N.Y: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1985), 17.

[23] Zizioulas, 18.

[24] Smith, Desiring the Kingdom, 43.

[25] Smith, 51, emphasis original.

[26] James K. A. Smith, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2016), 29.

[27] Charles Duhigg, Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, Random House Trade Paperback Edition (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2014), 17–18.

[28] Strawn and Brown, “Liturgical Animals: What Psychology and Neuroscience Tell Us about Formation and Worship,” 5.

[29] Strawn and Brown, 6.

[30] Strawn and Brown, 11.

[31] “Stakeholder Mapping and Analysis | Better Evaluation,” accessed October 28, 2023, https://www.betterevaluation.org/methods-approaches/methods/stakeholder-mapping-analysis.